Gut issues? Start here.

We’ve all had minor digestive complaints from time to time, but ongoing issues like bloating, heartburn, excessive gas, loose stools, constipation, and stomach cramping are not normal. And guess what? You don’t have to live with them! In fact, these symptoms are clear messages from your body that something is not right. In this article, I’ll share 8 tips to improve digestion, why it’s important to get to the root cause of digestive dysfunction, and how to better understand what your body is telling you.

Let’s start with the basics

Here’s a quick rundown of the phases of digestion:

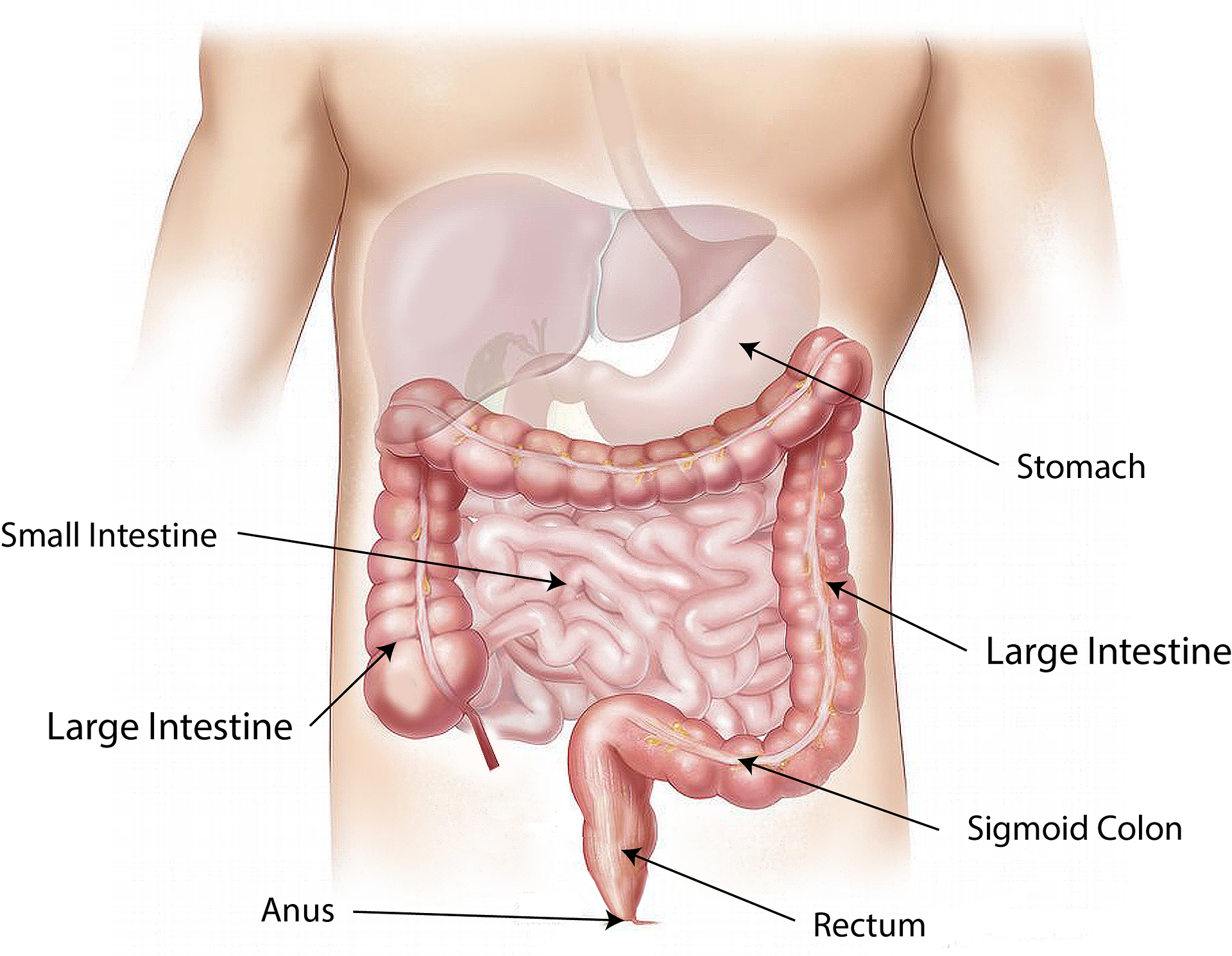

Smelling and thinking of food begins the digestive process with salivation.

In the mouth, saliva and chewing begins to breakdown food before it travels to the stomach.

Food enters the stomach, where acid and digestive enzymes break down food.

In the small intestine, bile and pancreatic enzymes break down the food further into small enough fragments to be absorbed in the bloodstream and delivered to cells.

5. In the large intestine, bacteria breaks down remaining food particles and produce small amounts of vitamin K and B vitamins. Here, some useful substances are absorbed into the bloodstream. Toxins can also move into the bloodstream from here, particularly if fecal matter is moving through too slow1.

3 major factors affecting digestion:

digestive secretions, stress and our nutrition

DIGESTIVE ENZYMES & GASTRIC ACID

The stomach’s pH is naturally around 1.0-2.5, which is highly acidic. An acidic stomach environment is very important for three key functions: 1.. to breakdown proteins 2. to stimulate the release of digestive enzymes and 3. to inhibit the growth of "bad" bacteria2. That’s right, acidity is good in the stomach, and actually necessary! Our stomachs need to be acidic, otherwise, we do not digest food properly. What’s more? Insufficient breakdown of food in the stomach can cause food to stay in the stomach longer, causing bloating a prolonged feeling of fullness, and yes, can even cause reflux (heartburn)1.

Unfortunately, the symptoms of both high and low stomach acid are very similar, but suffering from low stomach acid (hypochlorhydria) is more common. Why? For one thing, we secrete less gastric acid as we age. Vegetarian and low-protein diets can also lead to low stomach acid as well because zinc (which is commonly deficient in vegetarians) and protein are required to produce gastric acid and digestive enzymes1. You can do the simple DIY stomach acid test to find out if your stomach acid is low in my free Better Digestion Mini eBook.

WHAT WE EAT

There are plenty of foods that contribute to healing the stomach lining, improving digestion and enhancing the microbiome, like lacto-fermented foods (sauerkraut, kimchi, miso, kefir), prebiotic foods (blueberries, vegetables, nuts and green tea) and anti-inflammatory foods (turmeric, ginger, and colorful veggies)3. Unfortunately, most of us are consuming the ones that can damage the gut environment. Alcohol, gluten and sugar are some of the worst offenders1. My Mediterranean Diet Guide & Cookbook is packed full of gut-happy foods.

Gluten side note: As some of you know I am a baker, so I just have to elaborate here. Gluten is a protein that is known to damage cells that line the gut. Yes, it’s sad but true. There is a possible caveat for sourdough, however (yes!). Limited, but compelling research has shown sourdough (that has fermented at least 8 hours) reduces the non-digestible oligosaccharides fructans and raffinose (FODMAPS) increasing tolerability for those with IBS (irritable bowel syndrome). It also showed reduced flatulence and increased bifidobacteria (good gut bacteria) when compared with non-fermented bread consumption4.

This makes good sense; we know the fermentation process helps break down gluten, so of course, it would be easier to digest. That’s not to say sourdough consumption is for everyone, but if you have a mild reaction to wheat and haven’t yet experimented with sourdough, it may be worth investigating.

STRESS

Yes my friends, the gut-brain connection is real! And the implications are vast…research has found that the bidirectional communication between the brain and the digestive environment is in part controlled by our microbiota5. Via the vagus nerve, the brain can impact the gut and vice versa, and these changes influence and are influenced by the type of bacteria that populate the gut microbiome. In many cases, mental stress diminishes the good bacteria, which can cause digestive symptoms, further disrupting brain-gut communication and thus creating a vicious cycle.

The bottom line? Try to reduce stress, and consider regulating your vagus nerve. You can start by take stock of the major sources of stress in your life. Minimize the stress if you can, and consider practicing stress-reducing activities like spending time in nature, diaphragmatic breathing or mindful eating. At the very least, endeavor to eat in a peaceful environment, without distractions or stress…your gut will thank you for it!

Delicious, fermented kimchi

8 Tips to Improve Digestion

Avoid drinking beverages while eating (small sips are ok). Refrain from drinking 20 minutes before and 1 hour after eating. Why? Liquids dilute our precious digestive secretions, which can impair digestive processes.

Begin your meal with bitter greens like arugula (rocket), dandelion greens or radicchio with a squeeze of lemon. This stimulates digestive processes and gets your all-important bile moving.

Chew your food thoroughly, aim for 20-30 chews per bite and eat mindfully. Focus on the smell and taste of your food, and avoid distractions and stress which can impair digestive secretions.

Eat 2-4 tablespoons of lacto-fermented foods with each meal (sauerkraut, lime pickle, kimchi, kefir, miso) *hint, if these foods make you feel bad, you might have SIBO, and testing is recommended.

Find out if you are secreting sufficient stomach acid by doing the DIY stomach acid test found in the Digestion eBook.

Look at your bowel movements before you flush. What type do they tend to be on the Bristol Stool Chart? The ideal stool is type 4 – look at the color and texture; lighter, tan stool suggests impaired fat digestion/impaired bile secretion, while loose stools suggest food is moving too quickly through the system which impairs nutrient absorption. Harder stools suggest waste is staying in your digestive tract too long, which causes toxins to be reabsorbed by the bloodstream.

Do the transit time test to see how quickly food is moving through your system. Both the Bristol Stool Chart and the DIY Transit Time Test is included in the free eBook HERE. There you’ll find optimal transit times and why it’s important. If you discover you have a long transit time, check out my free guide for sluggish bowels: 7 Tips for Sluggish Bowels.

Identify food triggers – this is really important! If you have had chronic gut issues that come and go and you think you might have food allergies, you may have increased intestinal permeability as well (which can both cause and be caused by reactions to certain foods and immune over activity). If this is the case, you should identify and remove the offending foods while you heal the stomach lining. The elimination and reintroduction diet is the gold standard for identifying which foods need to be removed, but other tests, such as antibody testing and SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) tests may be appropriate for you. After you've healed, most people can add those foods back into their diets (unless they are lactose intolerant or have gluten sensitivities).

I challenge you to take on these recommendations to improve your digestion

They are the perfect first steps in getting to the root of your gut issues.

If you’ve already tried a million things and nothing is working, it might be time to work with a professional. Understanding root cause is key, because if you don’t know what is causing your symptoms, you can’t truly fix the dysfunction. It’s like throwing water randomly to put our a fire you can’t see….or in some cases, throwing antacids into an already low-acid stomach….which is NOT helping things, trust me! Chronic gut issues can lead to increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut), food sensitivities, and malabsorption and nutrient deficiencies which can have far reaching consequences in other body systems.

Yours in health,

Camille Hoffman

Naturopath, Nutritionist & Medical Herbalist

Book Your Free Discovery Call Here

The views and nutrition, naturopathic and herbal recommendations expressed by Camille Hoffman and Hoffman Natural Health’s programs, website, publications and newsletters, do not constitute a practitioner-patient relationship, are not intended to be a substitute for conventional medical service and are for informational purposes only. The statements and content found in these programs, website, publications and newsletters have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The treatments described may have known and unknown side effects and health hazards. Each user is solely responsible for their own healthcare choices and decisions. Camille Hoffman advises the website user to discuss these ideas with a healthcare professional or physician before trying them. Camille Hoffman does not accept any responsibility for any positive or adverse effects a person claims to experience, directly or indirectly, from the ideas and contents of this website.

SOURCES

Hechtman, L. (2019). Clinical Naturopathic Medicine E2. Elsevier.

Evans, D. F. et al. (1988). Measurement of gastrointestinal pH profiles in normal ambulant human subjects. Gut, 29(8), 1035-1041. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.29.8.1035

Murray, M., & Pizzorno, J. (2005). The encyclopaedia of healing foods. Atria Books.

Dimidi, E. et al. (2019). Fermented foods: definitions and characteristics, impact on the gut microbiota and effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. Nutrients, 11(8), 1806. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081806

De Palma, G. et al. (2014). The microbiota–gut–brain axis in gastrointestinal disorders; stressed bugs, stressed brain or both? The Journal of physiology, 592(14), 2989-2997. doi: https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273995